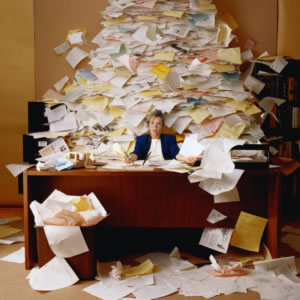

Leaders often believe that success means working themselves to the bone and wear busy-ness almost as a badge of honour. Yet all the evidence contradicts this way of thinking. As a Stanford University study showed: ‘Output falls sharply after a 50-hour work-week, and falls off a cliff after 55 hours – so much so that someone who puts in 70 hours produces nothing more with those extra 15 hours’.

I saw another interesting example of how busy-ness can be counter-productive in my own former organization, Flight Centre. This large global travel retailer put over 2000 of their top performers through an electronic test that measured energy as a human performance indicator. Ninety-five per cent failed, including the entire executive team. On analysis, it was discovered that the test measured consistent performance yet high achievers actually work as sprinters. They work in spurts, rest, and then go again. Constant activity was counter to their achievement.

Socrates warned us about this over 2000 years ago when he said: ‘Beware the barrenness of a busy life’. Despite this, many of us are working longer and longer hours, swapping sleep for ever-consuming tasks, and many organisations still encourage ‘busy-ness’ rather than productivity. The rise of mobile devices has led to the ‘24 hour workplace’ with the average employee sending or receiving 112 emails per day . We’re also being besieged in our private lives too. Families with both parents working are now 43% higher than just eight years ago. All this busy-ness is taking a toll on our health, leading to impaired sleep, depression, heavy drinking, diabetes, impaired memory, and heart disease. In effect, many of us are becoming ‘human doings’, rather than ‘human beings’ or to steal the latest corporate buzzword, we are now ‘disrupting’ ourselves.

Yet there are some practical solutions to this dilemma. Once a leader realises that activity doesn’t equate to achievement, then they can consciously start working ‘on the business’ and not just in it. This involves applying some discipline around the use of technology. With more than 300 technology addiction clinics in South East Asia alone, this is becoming a pressing issue. Digital detox holidays, apps teaching mindfulness and net-blocking software that can be set on timer are just a few of the answers here.

It also involves taking deliberate ‘time out’ for reflection. Mozart, Picasso and Churchill were dedicated walkers for precisely this purpose. Bill Gates is renowned for his “Think Weeks’ for which he credits many of Microsoft’s greatest inventions. Benjamin Franklin devoted an hour a day for learning, to fuel his success.

And finally it requires a degree of firm boundary-setting with colleagues and acquaintances. As billionaire CEO Warren Buffett discovered: ‘The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say ‘no’ to almost everything.’ In our now high-demand, rapid-changing world, this skill may never have been more vital.